Learned & unlearned helplessness in human babies and toddlers

As we are deep into yet another Covid winter alone at home with a 1-yr old and a hyperactive 6-yr old, I find myself contemplating the way little humans relate or don’t relate to our mammalian relatives at similar ages. Basic life functions such as locomotion, eyesight development, and the ability to hunt or feed are absolutely critical in the wild, and much less so in 2022 in the developed world, though I can point to numerous examples where fully-grown humans seem to get on just fine without much development in these three areas. Nevertheless, it seems that the animal world consistently raises and trains their young in basic life skills much sooner than we humans do.

Let’s start with locomotion in human babies vs other mammals. The large, grazing mammals are often able to walk or even run one week after birth. Giraffes, for example are famous for their ability to “walk” only 24 to 48 hours after birth. The motion is quite awkward at first, as you might expect, but this is what is required to survive in the grasslands with numerous predators on the prowl. The same goes for cows, sheep, gazelle, zebra and more, who must all gain the ability to move independently in order to keep up with the herd. There are species in other environments, such as deer, that are able to evade predators by hiding their young in trees and brush, so may take longer to develop independent locomotion. Then there are the predators such as wolf pups and eagles, whose young take from 2 weeks (wolves) and 10-14 weeks (eagles) to begin walking and flying, respectively. These predators don’t have to worry so much about threats to their young.

In humans, our larger brain mass seems to be directly correlated with the increased time to get moving, as shown in this paper in the journal Neurobiology. Our advanced bipedal movement takes considerable nerual wiring to achieve, and this wiring takes time to develop. Interestingly, rather than complete this development in the womb, it’s actually an advantage that babies are born with those squishy, mishapen skulls, otherwise child birth would be much more painful! Humans also have to develop the motor skills to hold and use tools, manipulate objects, and learn new styles of locomotion as they grow. According to Scientific American, a human fetus would have to complete an 18-21 month gestation period to be born at a similar developmental stage as a newborn chimpanzee. I suppose we can give babies a pass on the time to start walking.

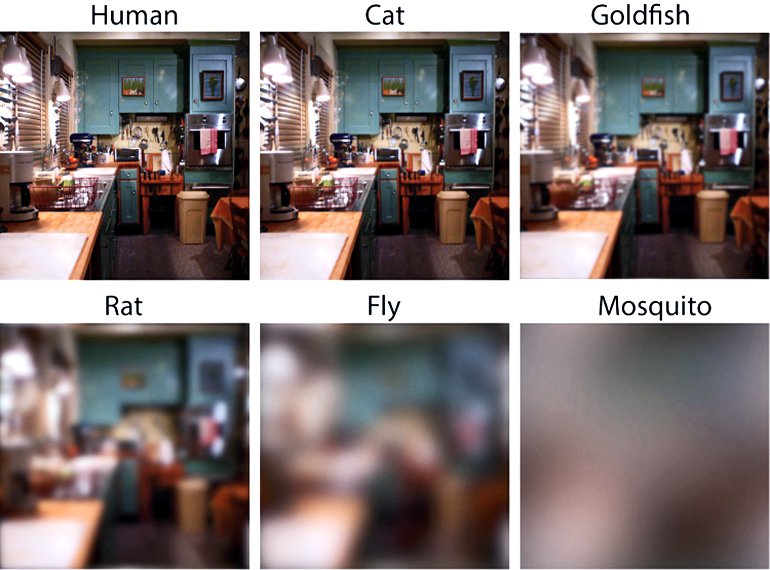

Next, let’s take a look at eyesight development as the next helpless state of development. Not everyone knows this, but babies are born with eyes that focus to the distance of the parent’s face, or generally about 8-10 inches away. Newborn babies are also unable to move their eyes between two images and will often have lazy or crossed eyes for the first few months as those neural circuits and muscles are strengthened. The human eye is actually quite remarkable in the animal kingdom and could standalone as a topic for its own post, but let’s look at the highlights:

- 100° (V) x 120° (H) field-of-view, binocular

- 100:1 contrast ration

- 1014 detectable luminance range

- estimated resolution of 576 megapixels

A 2018 study in Trends in Ecology & Evolution showed that human visual acuity and sharpness compares favorably out of 600 species studied. The study measured visual acuity in cycles per degree, or “the number of black and white parallel lines an animal can identify in one degree of their field of vision”. [Smithsonian Mag] Human visual acuity is around 60 cycles per degree, whereas a Wedge-Tailed Eagle can see 140 cycles per degree, and most insects are lucky to see 1 cycle per degree. Looks like human babies get a pass on eyesight development too.

Now let’s take it up a notch and look at animals vs toddlers’ ability to feed themselves. This is a point of particular frustration at my household, as the 6-yr old consistently has trouble not only collecting the basic ingredients of a meal once-prepared for him, but also has difficulty getting the food to his mouth without resorting to face-first gorging like at a death-row inmate’s final meal. Some studies have shown that babies, when left to develop their own eating habits with an unlimited food supply, will overeat and become less fussy about what they eat. On the other hand, it was shown in a 2017 control trial in JAMA Pediatrics that the so-called “baby-led approach to feeding” did not lead to any measurable different in BMI vs a tradition spoon-feeding approach. If I could find a method that consistently leads to less fussy eaters in children, I would buy every book on that subject that’s written. My children seem to have developed a lex non scripta at the dinner table:

- Differing foods shall not touch

- No more than two colors on the plate

- Unlimited ketchup

- No spices allowed

Clearly all domesticated animals similarly rely on human-led feeding to various degrees, in many cases for their entire lives. This differs from the young of predators and prey in the wild, who must quickly learn the rules of hunting, storing, resupplying and protecting a food supply. Many of these simple rules are completely lost on supermarket societies. In some sense this can be chocked up to what we now call “civilization” or the ability to feed vast non-farming classes with industrialization, domestication and mechanization. See Guns, Germs and Steel by Jared Diamond.

Regardless of the origin of the food, I don’t think it requires too much advanced cognitive development for kids to collect food from storage (fridge), complete any simple prep (plating), eat in a civilized way and clean up. Yet it takes years and years for little humans to master these tasks. God help them if the adults weren’t around to shepherd them into productive adulthood.