Managing Hardware Engineering in a Pandemic

March 2020 was a remarkable month. My company was making great strides in the early weeks. We were fortunate to close another round of funding and operating as usual, in-person, hosting consultants and working in the labs. On March 11 I held a call with the hardware engineering team about the possibility of a stay-at-home requirement and the need to shut down lab operations. It seemed like some of our team thought the discussion was premature, but it was followed up by a call the next day with our full leadership team. Keep in mind at this point there were 1600 cases in the whole country, and about 100 cases in Massachussetts. The NBA had apparently found some cases among their players and decided the cancel the whole season.

By March 19 California had issued a stay-at-home advisory, followed by New York, Connecticut and New Jersey. It was only a matter of time. Sure enough, the MA Governor issued the advisory for all non-essential businesses closed starting March 24 through April 7 (this would later be extended). We knew this would last much longer than a couple of weeks and had to refine a work plan for what we now call the “new normal”. Ultimately, a smooth-running, remote hardware engineering team should revolve around four key concepts: efficient and effective communication, streamlined logistics, networked systems, and data.

Preface: At MultiSensor Scientific, we are in the development stage on a complex industrial imaging product, so it’s not like we’re cranking out widgets from a CM.

Communication

Articles on effective business communication are a dime a dozen and get rewritten with every new business communication tool that comes out. Our engineering team has tried several tools over the years to streamline planning and execution throughout the product development process. We already had engineers scattered around New England and Western Canada, some who prefer email, some prefer texting, others more savvy on Slack. The biggest stumbling block for our mixed hardware/software team has been the often divergent nature of waterfall vs agile development processes.

Regardless of the communication tools used, during the current crisis and while our labs were officially shutdown, we found most success when leaning into some tried-and-true communication practices:

- Block out time (especially for planning activity and non-technical discussion)

- Calendar transparency - everyone’s work calendar is shared across the organization. If you’re unavailable, block out some time.

- Dedicated messaging channels!

Let’s expand on number 3. The emergence of Slack, which is attempting to replace email as the repository of business communication record is well documented. Each communication platform has strengths and weakesses (email vs text vs video chat vs Slack, etc). We’ve found during the pandemic that email is the best option outside the organization and when composing longer messages that won’t spur discussion. Slack is best for private messaging, extended 1-1 or 1-2 debug sessions, and social communication. This can easily shift to a video call for unscheduled screen-sharing for instance. Heavy use of Slack channels also makes such discussion transparent to all subscribers. Easy enough to mute a channel if you need to, but it avoids the situation where a technical email is sent out to a chosen few and a critical contributor is left out of the loop. Texts are best left for emergencies when you know someone is not in front of email or Slack. We ran into many of these situations, with parents of young kids suddenly conducting home school sessions during the workday and juggling other responsibilities during the shutdown.

Logistics

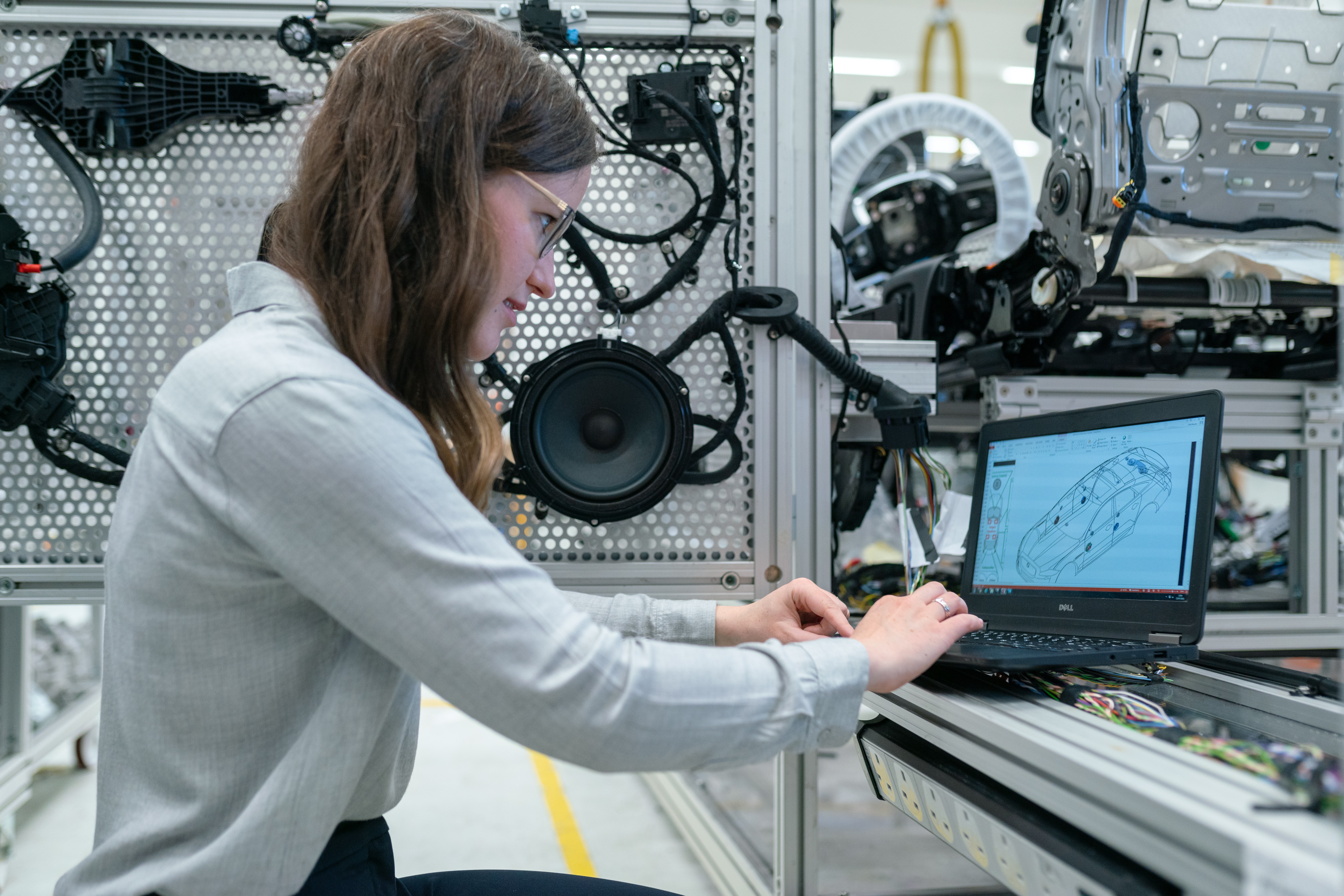

If my notes on communication during the pandemic sounded pretty boilerplate to the modern engineer, the next two topics are where things get trickier. How do you make progress on a highly technical piece of hardware when not all contributors can simultaneously have access? When an engineer needs to work hands-on with the equipment (EE working on a new PCB that was just fabricated, MEs inspecting new 3D printed parts that came off the printer) the solution is to streamline logistics.

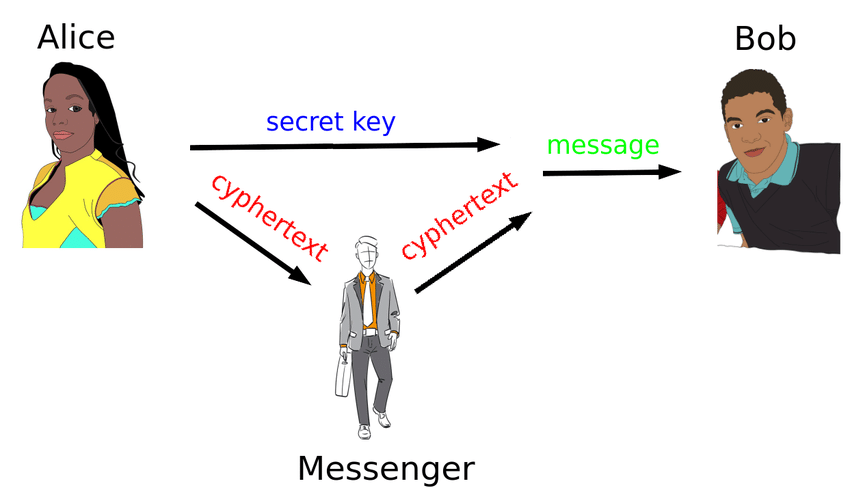

While the labs and offices are shutdown, there is no longer a central hub for physical parts to live and operate. If, as in our case, the hardware system is relatively large and complex such that not every engineer gets a copy, the system has to make the rounds to each person at a dedicated stage of development. This means that no time can be lost in getting it from one person to the next. Let’s consider Alice and Bob, two engineers who each need to test some new system components on one existing prototype. They can’t both use the system the same day because they’re locked down in different locations (thanks Covid). If they can’t both validate their parts in 2 days, a milestone slips.

Following best communication practices, Alice updates the right person(s) about progress, then shipping docs are generated for Bob, who needs it next. Thanks to the remote office manager, let’s call her Mary, all logistical docs are generated and sent over to the right person at the right time. Each person working with hardware also has a supply of packing materials and has been instructed on best shipping practices and same-day shipping deadlines so it all goes smoothly. When Alice is done, the package ships next-day to Bob so he can test his changes and “deploy” updates to the field engineer, who still gets to do field work because he’s in Canada and they haven’t completely botched their coronavirus response.

Networked systems

Now, there are ways to have multiple developers working on a single prototype at a time. This involves robust networking infrastructure to give remote users access to a single system from anywhere in North America. I may go deeper into discussion of our infrastructure stack in another post, but during the present crisis, it involves remote developers getting secure access to the home network of the hardware engineer, whereas this used to take place over the secure network at the office. The hardware system has a network connection, and the software developer has access to that network to monitor logs, deploy updates and troubleshoot. Pretty standard stuff, but all of a sudden this needs to happen across people’s home networks, which is what would’ve happened pre-covid if we were still operating out of a garage!

One additional note, which is widely known in software and embedded systems development but bears repeating, is the importance of logging. One popular logging stack is the so-called ELK stack, consisting of Elastic Stack for centralized logging and searching, Logstash for data processing and Kibana for visualization. While logs are very useful in the early stages of development to see when/why a continuously-operating system may have failed, logs are critical after those first few prototypes scale to production and are operating continuously across the globe.1

Data, data, data

This one flows naturally from the other three concepts discussed, but has particular importance in the context of engineering management during a pandemic. In additional to smooth communication, logistics and system networking, a team of engieers needs transparent and timely access to data generated from systems under development. Is a motor overheating? Get the data. Why does a docker container fail to load? Get the data? Why does the camera generate a funny image artifact only when it’s outdoors? Data, data, data.

Data! Data! Data! I can’t make bricks without clay! - Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

During the team’s regular technical discussions, a design of experiments may be required to answer a particularly sticky questions. All data generated from those experiments should be analyzed, distilled and shared at the next available opportunity. The key here is not to just data dump on the entire team, who are of course busy with their own tasks. The key is for the relevant people to analyze system data and have charts/plots/raw data as backup during a review.

Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted. - Albert Einstein

It is this quick build-test-review cycle that is strained by having a fully remote hardware engineering team, but with= streamlined communications, logistics and data analysis the challenging circumstances can be overcome.